Hello and welcome to Episode 7 of Read Paradise Lost with me, Jane Davis, a podcast and Substack newsletter about my project to read all of Paradise Lost by John Milton, aloud, and with a sometimes word-by-word, sometimes line-by-line discussion. This is one-take recording with no editing, so forgive noise of seagulls, my coughing, or sound of men drilling next door. Rough and ready reading is what you get.

See Episode 1 for an introduction to the project.

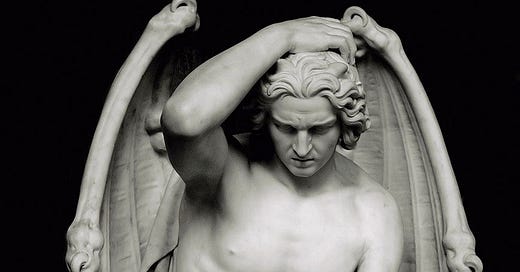

The Genius of Evil (Lucifer) 1848, Marble, St Paul’s Cathedral, Liege, Belgium, by Guillame Geefs. The chains, the apple, the diadem and a broken sceptre surround or adorn a beautiful, distressed, male figure, wrapped in bat-like wings. A first - and remarkably similar - go at this commission, by Guillame’s brother, Joseph, was removed from the Cathedral on the grounds of its ‘distracting allure and unhealthy beauty.’ See wikipedia.

This week we’re reading Book 1, lines 192 to 270, and we begin with Milton giving us this physical description of Satan, followed by Satan looking about then speaking:

Thus Satan talking to his neerest Mate

With Head up-lift above the wave, and Eyes

That sparkling blaz'd, his other Parts besides

Prone on the Flood, extended long and large [ 195 ]

Lay floating many a rood, in bulk as huge

As whom the Fables name of monstrous size,

Titanian, or Earth-born, that warr'd on Jove,

Briareos or Typhon, whom the Den

By ancient Tarsus held, or that Sea-beast [ 200 ]

Leviathan, which God of all his works

Created hugest that swim th' Ocean stream:

Him haply slumbring on the Norway foam

The Pilot of some small night-founder'd Skiff,

Deeming some Island, oft, as Sea-men tell, [ 205 ]

With fixed Anchor in his skaly rind

Moors by his side under the Lee, while Night

Invests the Sea, and wished Morn delayes:

So stretcht out huge in length the Arch-fiend lay

Chain'd on the burning Lake, nor ever thence [ 210 ]

Had ris'n or heav'd his head, but that the will

And high permission of all-ruling Heaven

Left him at large to his own dark designs,

That with reiterated crimes he might

Heap on himself damnation, while he sought [ 215 ]

Evil to others, and enrag'd might see

How all his malice serv'd but to bring forth

Infinite goodness, grace and mercy shewn

On Man by him seduc't, but on himself

Treble confusion, wrath and vengeance pour'd. [ 220 ]

Forthwith upright he rears from off the Pool

His mighty Stature; on each hand the flames

Drivn backward slope thir pointing spires, and rowld

In billows, leave i'th' midst a horrid Vale.

Then with expanded wings he stears his flight [ 225 ]

Aloft, incumbent on the dusky Air

That felt unusual weight, till on dry Land

He lights, if it were Land that ever burn'd

With solid, as the Lake with liquid fire;

And such appear'd in hue, as when the force [ 230 ]

Of subterranean wind transports a Hill

Torn from Pelorus, or the shatter'd side

Of thundring Ætna, whose combustible

And fewel'd entrals thence conceiving Fire,

Sublim'd with Mineral fury, aid the Winds, [ 235 ]

And leave a singed bottom all involv'd

With stench and smoak: Such resting found the sole

Of unblest feet. Him followed his next Mate,

Both glorying to have scap't the Stygian flood

As Gods, and by thir own recover'd strength, [ 240 ]

Not by the sufferance of supernal Power.

Is this the Region, this the Soil, the Clime,

Said then the lost Arch-Angel, this the seat

That we must change for Heav'n, this mournful gloom

For that celestial light? Be it so, since he [ 245 ]

Who now is Sovran can dispose and bid

What shall be right: fardest from him is best

Whom reason hath equald, force hath made supream

Above his equals. Farewel happy Fields

Where Joy for ever dwells: Hail horrours, hail [ 250 ]

Infernal world, and thou profoundest Hell

Receive thy new Possessor: One who brings

A mind not to be chang'd by Place or Time.

The mind is its own place, and in it self

Can make a Heav'n of Hell, a Hell of Heav'n. [ 255 ]

What matter where, if I be still the same,

And what I should be, all but less then he

Whom Thunder hath made greater? Here at least

We shall be free; th' Almighty hath not built

Here for his envy, will not drive us hence: [ 260 ]

Here we may reign secure, and in my choyce

To reign is worth ambition though in Hell:

Better to reign in Hell, then serve in Heav'n.

But wherefore let we then our faithful friends,

Th' associates and copartners of our loss [ 265 ]

Lye thus astonisht on th' oblivious Pool,

And call them not to share with us their part

In this unhappy Mansion, or once more

With rallied Arms to try what may be yet

Regaind in Heav'n, or what more lost in Hell? [ 270 ]

Satan is of epic proportions, we see, and we are thus asked implicitly to remember other epic works (familiar to Milton and to most of his contemporary readers, but less so to us, so have a look at the notes in the Dartmouth online text):

Thus Satan talking to his neerest Mate

With Head up-lift above the wave, and Eyes

That sparkling blaz'd, his other Parts besides

Prone on the Flood, extended long and large [ 195 ]

Lay floating many a rood, in bulk as huge

As whom the Fables name of monstrous size,

Titanian, or Earth-born, that warr'd on Jove,

Briareos or Typhon, whom the Den

By ancient Tarsus held, or that Sea-beast [ 200 ]

Leviathan, which God of all his works

Created hugest that swim th' Ocean stream:

And finally, after the side-glances at Virgil and Hesiod, a piece of natural history epic in the form of the whale, Leviathan:

Leviathan, which God of all his works

Created hugest that swim th' Ocean stream:

Him haply slumbring on the Norway foam

The Pilot of some small night-founder'd Skiff,

Deeming some Island, oft, as Sea-men tell, [ 205 ]

With fixed Anchor in his skaly rind

Moors by his side under the Lee, while Night

Invests the Sea, and wished Morn delayes:

How big is he? As big as a whale a sailor might mistake for an island, and dangerous too, as we struggle to get through the night, wishing for morning… that’s how big and bad he is:

So stretcht out huge in length the Arch-fiend lay

Chain'd on the burning Lake, nor ever thence [ 210 ]

Had ris'n or heav'd his head, but that the will

And high permission of all-ruling Heaven

Left him at large to his own dark designs,

That with reiterated crimes he might

Heap on himself damnation, while he sought [ 215 ]

Evil to others, and enrag'd might see

How all his malice serv'd but to bring forth

Infinite goodness, grace and mercy shewn

On Man by him seduc't, but on himself

Treble confusion, wrath and vengeance pour'd. [ 220 ]

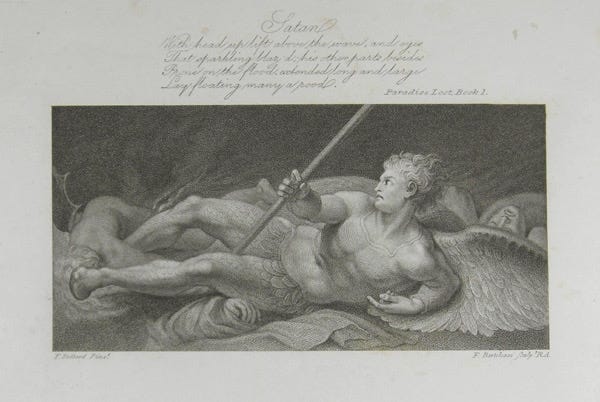

Satan on the burning lake, 1825. John Martin (1789 - 1854)

This is a moment we’re going to have to hold in mind as we go on with the poem, a moment that gives many readers deep pause. Satan was ‘Chain'd on the burning Lake’ but God lets him go free:

the will

And high permission of all-ruling Heaven

Left him at large to his own dark designs

Two things to note- first ‘will’ of heaven and second ‘high permission’ of heaven. Neither of which Satan seems to note - indeed, the question of how the chains drop from him does not seem to cross his mind. From Milton’s point of view, from the poem’s, the freedom of Satan is a choice made by God. And why?

That with reiterated crimes he might

Heap on himself damnation, while he sought [ 215 ]

Evil to others, and enrag'd might see

How all his malice serv'd but to bring forth

Infinite goodness,

Does God want the heaped damnation, does he want the enragement? Are they natural by-products of Satan’s own malice? Or should we be going to the verb ‘serv’d’? (which seems to counteract ‘sought’). Certainly, these lines have caused a lot of unease in readers (take a look at William Empson’s book, Milton’s God) who feel God is not good here, but I’m looking for what Milton might have meant, and I think he leaves the blame in the person doing the act, in Satan. He chooses bad, and the rage that ensues when he sees good come out of it must be his own responsibility. Yet it gets worse:

…all his malice serv'd but to bring forth

Infinite goodness, grace and mercy shewn

On Man by him seduc't, but on himself

Treble confusion, wrath and vengeance pour'd. [ 220 ]

Line 218, ‘infinite goodness, grace and mercy shewn’ has a wonderfully calm rhythm which momentarily reassures me that God is indeed good, but then we come to the ‘treble confusion, wrath and vengeance pour'd’ which puts me squarely face to face with an unforgiving vengeance-seeking God. I have to accept this is not the God I might want to seek, but Milton is happy with him. Why, readers must ask, is ‘infinite goodness, grace and mercy shewn’ to man and only ‘confusion, wrath and vengeance’ poured on Satan? The key is perhaps in the word ‘seduc’d’. Satan rose against God of his own volition; man was seduced into disobedience.

We need to know more! But in a second, all changes, and the chains are gone, and Satan rises:

Forthwith upright he rears from off the Pool

His mighty Stature; on each hand the flames

Drivn backward slope thir pointing spires, and rowld

In billows, leave i'th' midst a horrid Vale.

Then with expanded wings he stears his flight [ 225 ]

Aloft, incumbent on the dusky Air

That felt unusual weight, till on dry Land

He lights, if it were Land that ever burn'd

With solid, as the Lake with liquid fire;

And such appear'd in hue, as when the force [ 230 ]

Of subterranean wind transports a Hill

Torn from Pelorus, or the shatter'd side

Of thundring Ætna, whose combustible

And fewel'd entrals thence conceiving Fire,

Sublim'd with Mineral fury, aid the Winds, [ 235 ]

And leave a singed bottom all involv'd

With stench and smoak: Such resting found the sole

Of unblest feet. Him followed his next Mate,

Both glorying to have scap't the Stygian flood

As Gods, and by thir own recover'd strength, [ 240 ]

Not by the sufferance of supernal Power.

Wonderful image of the sea of flames parting, which Milton’s contemporaries would recognise as a kind of mirror image of the parting of the seas for the children of Israel - the waves of flame back off to create a way through and into the space Satan flies:

Then with expanded wings he stears his flight [ 225 ]

Aloft, incumbent on the dusky Air

That felt unusual weight,

A reader commented on the air having to take this unusual (huge) weight, and my note in the Fowler edition tell me, the moment recalls Spenser’s Faery Queene, (Book1, 10,18) where the weight was the weight of a dragon. Satan lands on fiery land and the visual images now are all of volcanoes, eruptions, ‘stench and smoak’.

I was somehow touched by the line:

Such resting found the sole

Of unblest feet.

I’m not sure why - perhaps thinking of Biblical feet, being washed, or sandalled, in stories of humility, as in Christ washing the disciples’ feet. A reader commented too on the word play in ‘sole’/soul. The pain of walking on fire. The resolution required to ignore it.

We see now that Satan and Beelzebub don’t realise that they are unchained by God’s will, as the last three lines show:

Both glorying to have scap't the Stygian flood

As Gods, and by thir own recover'd strength, [ 240 ]

Not by the sufferance of supernal Power.

Can they not tell, will they not allow that they have been released by a higher power? or are they simply not able to imagine such a thing? Either way, vaunting and crowing are quickly the order of the day…as they ‘glory’ in ‘thir own recover’d strength.’

Yet, as before, when Satan speaks, some of his words undercut that crowing.

Is this the Region, this the Soil, the Clime,

Said then the lost Arch-Angel, this the seat

That we must change for Heav'n, this mournful gloom

For that celestial light? Be it so, since he [ 245 ]

Who now is Sovran can dispose and bid

What shall be right: fardest from him is best

Whom reason hath equald, force hath made supream

Above his equals. Farewel happy Fields

Where Joy for ever dwells: Hail horrours, hail [ 250 ]

Infernal world, and thou profoundest Hell

Receive thy new Possessor: One who brings

A mind not to be chang'd by Place or Time.

‘This’ reiterated four times press home Satan’s terrible sense of loss but his resolute ‘be it so’ shows he is not going to consciously mourn that loss. He spins the facts (as Milton tells them) into some version he, Satan, can tolerate:

since he [ 245 ]

Who now is Sovran can dispose and bid

What shall be right: fardest from him is best

Whom reason hath equald, force hath made supream

Above his equals.

It seems that from Satan’s point of view, God is only recently or temporarily ‘sovran’ - he/who now is sovran’. They were, according to Satan, previously equals, but greater force on God’s part means he’s currently able to lord it above his equals. Just force. One needn’t respect that. Satan continues, himself centre stage, to make the place and situation his own:

Farewel happy Fields

Where Joy for ever dwells: Hail horrours, hail [ 250 ]

Infernal world, and thou profoundest Hell

Receive thy new Possessor: One who brings

A mind not to be chang'd by Place or Time.

His mind, he holds, is strong enough to withstand any torture. And now he makes his most astonishing claim, that the individual mind is the centre and ground of reality:

The mind is its own place, and in it self

Can make a Heav'n of Hell, a Hell of Heav'n. [ 255 ]

What matter where, if I be still the same,

And what I should be, all but less then he

Whom Thunder hath made greater? Here at least

We shall be free;

The modern consciousness, I am it, me at centre, I decide…at its worst a stuck unwillingness to accept any external reality, but at its best, a resolute determination to stick to one’s beliefs. To be self-determined … The poem asks us to hold the possibility that the mind really is its own place - which is patently true when one is alone. But are we alone in a universe where there is an all-knowing God? I’m moved, not by Satan the character, but by the predicament of a mind which wishes to be central (don’t all our minds work like that?) And for a mind committed to the centrality of self, freedom is as important as loss or suffering.

Here at least

We shall be free; th' Almighty hath not built

Here for his envy, will not drive us hence: [ 260 ]

Here we may reign secure, and in my choyce

To reign is worth ambition though in Hell:

Better to reign in Hell, then serve in Heav'n.

He won’t serve. That’s the fact. I remember back to the word ‘serv’d ‘ earlier - ‘all his malice serv'd but to bring forth/Infinite goodness’ (line 217/218) Milton has set the poem up so that he can demonstrate ‘the ways of God’ and the poem holds the view that God is both good and shaping ‘eternal providence’ for humans, but Satan still believes he has choice and can step outside of that providence. So once again, a call to action:

But wherefore let we then our faithful friends,

Th' associates and copartners of our loss [ 265 ]

Lye thus astonisht on th' oblivious Pool,

And call them not to share with us their part

In this unhappy Mansion, or once more

With rallied Arms to try what may be yet

Regaind in Heav'n, or what more lost in Hell? [ 270 ]

We get knocked down, but we get up again. You’re never going to keep us down. No, whispers God, silently, invisibly. Everything depends on you.

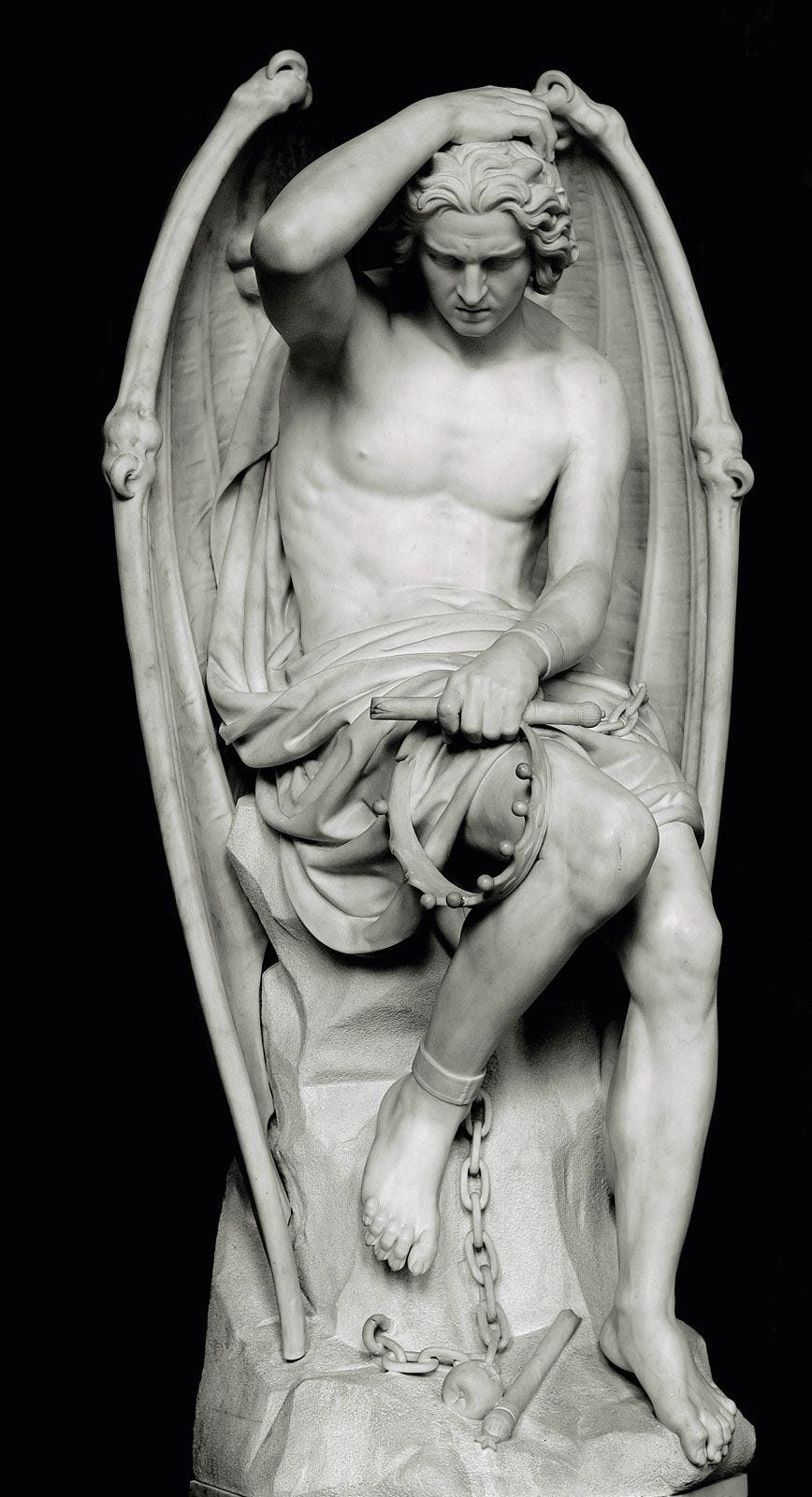

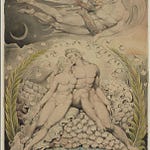

Satan, engraved by Bartolozzi c1822, is caught turning from angel to scaly devil. Around him the fallen angels writhe in confusion, their angelic wings turning bat-like

Share this post