Hello and welcome to Episode 59 of Read Paradise Lost with me, Jane Davis, a podcast and Substack newsletter about my project to read all of Paradise Lost by John Milton, aloud, and with a sometimes word-by-word, sometimes line-by-line discussion. This is a one-take recording with no editing, so forgive noise of seagulls, my coughing, or sound of men drilling next door. Rough and ready reading is what you get.

See Episode 1 for an introduction to the project.

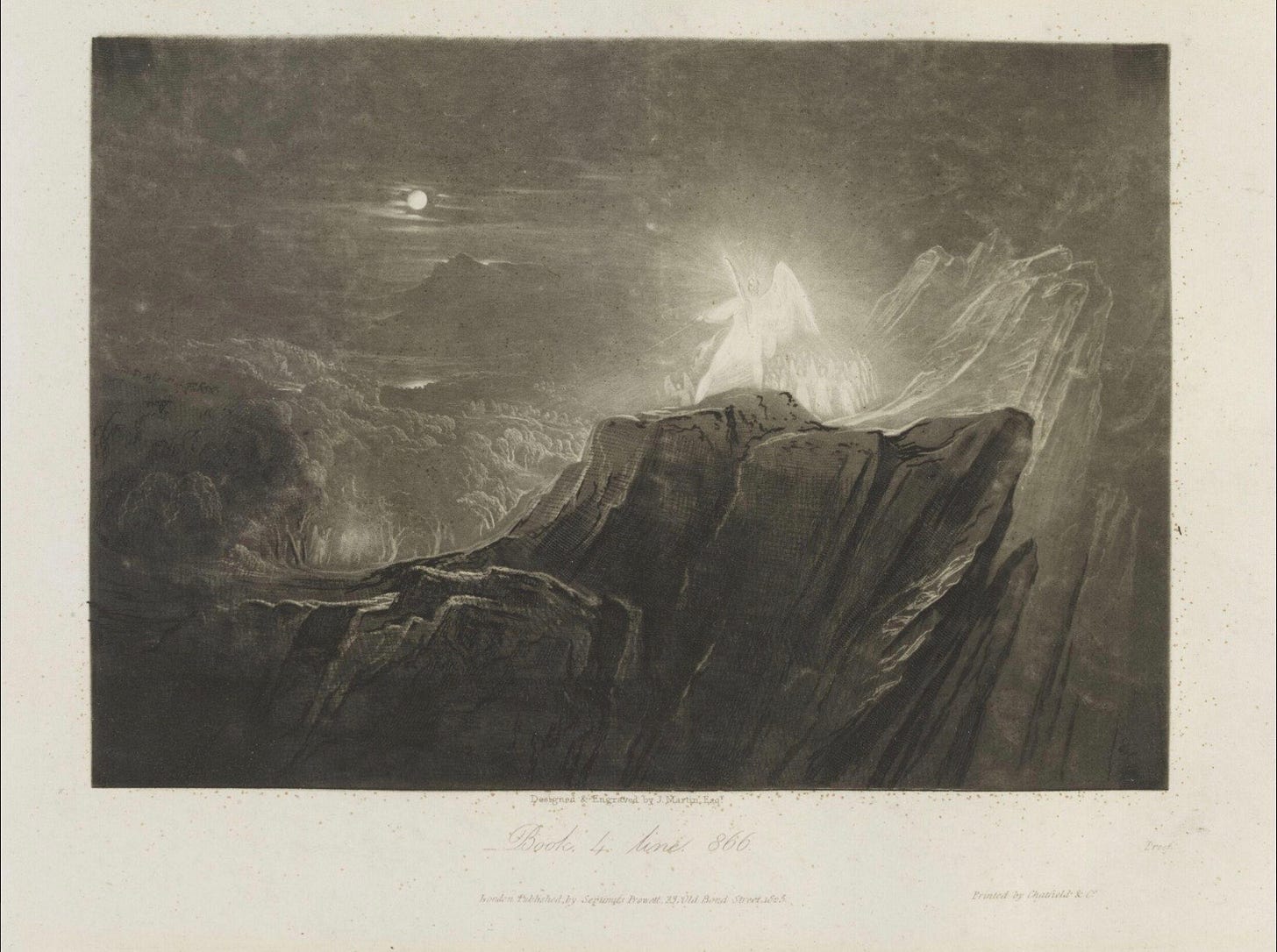

We approach the end of Book 4 now, and we will finish it next week. The portion is 110 lines this week. I’ll read it bit by bit but this week’s episode is speedy.

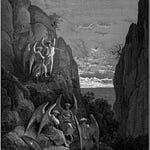

Here’s Satan arrested, as it were, by two junior Angels, Ithuriel and Zephon, who have made him feel ‘how awful goodness is’, and have told him being wicked makes him weak;

The Fiend repli'd not, overcome with rage;

But like a proud Steed reind, went hautie on,

Chaumping his iron curb: to strive or flie

He held it vain; awe from above had quelld [ 860 ]

His heart, not else dismai'd. Now drew they nigh

The western Point, where those half-rounding guards

Just met, and closing stood in squadron joind

Awaiting next command. To whom thir Chief

Gabriel from the Front thus calld aloud. [ 865 ]

I love this image of Satan ‘like a proud Steed reind’, with that sense of danger I am always aware of in a big horse, however ‘reind’ by captivity. There’s a nobility here, but it feels undercut by rage. Yes, he’s ‘hautie’ and that is his nature, which doesn’t change. Yes something is changed here - there is an ‘iron curb’, and because of it ‘to strive or flie/He held it vain’. Why?

These junior Angels, so low in the heavenly hierarchy as perhaps never even to have seen Satan, have quelled him by their proximity to God;

awe from above had quelld [ 860 ]

His heart, not else dismai'd.

That ‘above’ is God, but it is present in creatures Satan had despised as ‘nuttins’. Yet here it is : goodness. Awe-ful.

Gabriel hears them coming, and thinks it may be Satan, ‘but faded splendour wan’ clouds the recognition. We’re in a soldiers camp now, watching the arrival of a prisoner:

O friends, I hear the tread of nimble feet

Hasting this way, and now by glimps discerne

Ithuriel and Zephon through the shade,

And with them comes a third of Regal port,

But faded splendor wan; who by his gate [ 870 ]

And fierce demeanour seems the Prince of Hell,

Not likely to part hence without contest;

Stand firm, for in his look defiance lours.

He scarce had ended, when those two approachd

And brief related whom they brought, where found, [ 875 ]

How busied, in what form and posture coucht.

To whom with stern regard thus Gabriel spake.

Why hast thou, Satan, broke the bounds prescrib'd

To thy transgressions, and disturbd the charge

Of others, who approve not to transgress [ 880 ]

By thy example, but have power and right

To question thy bold entrance on this place;

Imploi'd it seems to violate sleep, and those

Whose dwelling God hath planted here in bliss?

The interrogation is straightforward, but we see that Gabriel has no idea what might be happening. Like all the other Good Angels we have seen so far, alongside or in conversation with Satan, he seems naive. Were you about to violate sleep? he asks first, and only second coming to ‘those/Whose dwelling God hath planted here in bliss…’ and no sense of how or what violation might be…His innocence makes Satan think that what seemed wise in heaven, may not now be so… and that innocence may give the great manipulator a way through;

To whom thus Satan with contemptuous brow. [ 885 ]

Gabriel, thou hadst in Heav'n th' esteem of wise,

And such I held thee; but this question askt

Puts me in doubt. Lives ther who loves his pain?

Who would not, finding way, break loose from Hell,

Though thither doomd? Thou wouldst thyself, no doubt, [ 890 ]

And boldly venture to whatever place

Farthest from pain, where thou mightst hope to change

Torment with ease, and; soonest recompence

Dole with delight, which in this place I sought;

To thee no reason; who knowst only good, [ 895 ]

But evil hast not tri'd:

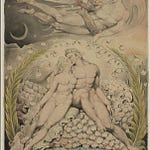

Satan’s point is a good one - knowing only Good (which might work perfectly in Heaven) is a limitation here, in a situation where evil is also present. Who’d stand pain if they could do otherwise? But you can’t understand that and besides

and wilt object

His will who bound us? let him surer barr

His Iron Gates, if he intends our stay

In that dark durance: thus much what was askt.

The rest is true, they found me where they say; [ 900 ]

But that implies not violence or harme.

The second part of the response is more aggressive - ‘let him surer barr/

His Iron Gates, if he intends our stay/In that dark durance’ - and also worrying for us and perhaps for the good Angels - for we know (do they?) that God knows this escape will happen, indeed, let it happen, because he cares more about Free Will than he does about any other aspect of those he has created.

Thus he in scorn. The warlike Angel mov'd,

Disdainfully half smiling thus repli'd.

O loss of one in Heav'n to judge of wise,

Since Satan fell, whom follie overthrew, [ 905 ]

And now returns him from his prison scap't,

Gravely in doubt whether to hold them wise

Or not, who ask what boldness brought him hither

Unlicenc't from his bounds in Hell prescrib'd;

So wise he judges it to fly from pain [ 910 ]

However, and to scape his punishment.

Gabriel’s response is simply this coolish disdain for the creature he sees before him and a powerful belief in the final overcoming for Evil by Good;

So judge thou still, presumptuous, till the wrauth,

Which thou incurr'st by flying, meet thy flight

Seavenfold, and scourge that wisdom back to Hell,

Which taught thee yet no better, that no pain [ 915 ]

Can equal anger infinite provok't.

And he goes on to wonder why Satan has come alone - don’t the others feel as he feels?

But wherefore thou alone? wherefore with thee

Came not all Hell broke loose? is pain to them

Less pain, less to be fled, or thou then they

Less hardie to endure? courageous Chief, [ 920 ]

The first in flight from pain, hadst thou alleg'd

To thy deserted host this cause of flight,

Thou surely hadst not come sole fugitive.

To which the Fiend thus answerd frowning stern.

Not that I less endure, or shrink from pain, [ 925 ]

Insulting Angel, well thou knowst I stood

Thy fiercest, when in Battel to thy aide

The blasting volied Thunder made all speed

And seconded thy else not dreaded Spear.

But still thy words at random, as before, [ 930 ]

Argue thy inexperience what behooves

From hard assaies and ill successes past

A faithful Leader, not to hazard all

Through wayes of danger by himself untri'd,

I therefore, I alone first undertook [ 935 ]

To wing the desolate Abyss, and spie

This new created World, whereof in Hell

Fame is not silent, here in hope to find

Better abode, and my afflicted Powers

To settle here on Earth, or in mid Aire; [ 940 ]

Though for possession put to try once more

What thou and thy gay Legions dare against;

Whose easier business were to serve thir Lord

High up in Heav'n, with songs to hymne his Throne,

And practis'd distances to cringe, not fight. [ 945 ]

Satan identifies more evidence of Gabriel’s innocence - he can’t know what leadership is:

But still thy words at random, as before, [ 930 ]

Argue thy inexperience what behooves

From hard assaies and ill successes past

A faithful Leader,

It’s harder doing this than being in Heaven, he argues, ‘with songs to hymne his Throne’. But now Gabriel begins to get the measure of him, and calls him out for what he is: a faithless liar;

To whom the warriour Angel, soon repli'd.

To say and strait unsay, pretending first

Wise to flie pain, professing next the Spie,

Argues no Leader, but a lyar trac't,

Satan, and couldst thou faithful add? O name, [ 950 ]

O sacred name of faithfulness profan'd!

Faithful to whom? to thy rebellious crew?

Armie of Fiends, fit body to fit head;

Was this your discipline and faith ingag'd,

Your military obedience, to dissolve [ 955 ]

Allegeance to th' acknowledg'd Power supream?

And thou sly hypocrite, who now wouldst seem

Patron of liberty, who more then thou

Once fawn'd, and cring'd, and servilly ador'd

Heav'ns awful Monarch? wherefore but in hope [ 960 ]

To dispossess him, and thy self to reigne?

But mark what I arreede thee now, avant;

Flie thither whence thou fledst: if from this houre

Within these hallowd limits thou appeer,

Back to th' infernal pit I drag thee chaind, [ 965 ]

And Seale thee so, as henceforth not to scorne

The facil gates of hell too slightly barrd.

The account of Satan in Heaven as a fawner, a cringer, a servile adorer is reminiscent of a modern day politics playbook. How to get to the top? Lie to your leader. Why fawn? To get close ‘To dispossess him, and thy self to reigne?’

It’s worth following the Dartmouth online edition footnote to ‘Patron of Liberty’

Patron of liberty. Satan may depict some of the disappointment Milton felt in another apparent patron of liberty, Oliver Cromwell. "In the spring of 1657 Cromwell was tempted by an offer of the crown by a majority in Parliament on the ground that it fitted in better with existing institutions and the English common law. In the end he refused to become king because he knew that it would offend his old republican officers. Nevertheless, in the last year and a half of his life he ruled according to a form of government known as the "Humble Petition and Advice." This in effect made him a constitutional monarch with a House of Lords whose members he was allowed to nominate as well as an elected House of Commons." (Encyclopedia Britannica, "Cromwell").

Satan gets off lightly here, as Gabriel simply tells him to leave (‘I arreede thee now, avant’).

Can you simply tell your terrible enemies to ‘go!’. They don’t usually.

The questions for me as I read this is -why isn’t Gabriel more aware of the dangers - how can he just let Satan go - why is a top-ranking Good Angel so naive?

And I answer myself : those who only know good cannot understand evil. Everything is as it is, and in this poem is part of a bigger pattern we can’t see. Adam and Eve must be tempted, because that is part of Freedom in a universe where there is evil as well as good. (Perhaps the question remains, why did Satan become evil? But that is not a question Milton puts into the poem. It is a given, for him.)

If I translate this into a real life scenario, I have to leave out the bigger pattern, as I’m not a Christian and can’t even glimpse such a thing. But I do know that good is often unable to imagine evil. And that once seen, and even called out, such evil may simply continue to bluff it out.

And if I imagine Milton, alone, broken, blind, disappointed having given half his life to a revolution he can no longer believe in, drawing on knowledge of interrogation of enemies as well as fears of such interrogations, this section seems earthly, human.

We will finish this exchange, and Book 4, next time, when there will be

more next week.

Share this post