Hello and welcome to Episode 56 of Read Paradise Lost with me, Jane Davis, a podcast and Substack newsletter about my project to read all of Paradise Lost by John Milton, aloud, and with a sometimes word-by-word, sometimes line-by-line discussion. This is a one-take recording with no editing, so forgive noise of seagulls, my coughing, or sound of men drilling next door. Rough and ready reading is what you get.

See Episode 1 for an introduction to the project.

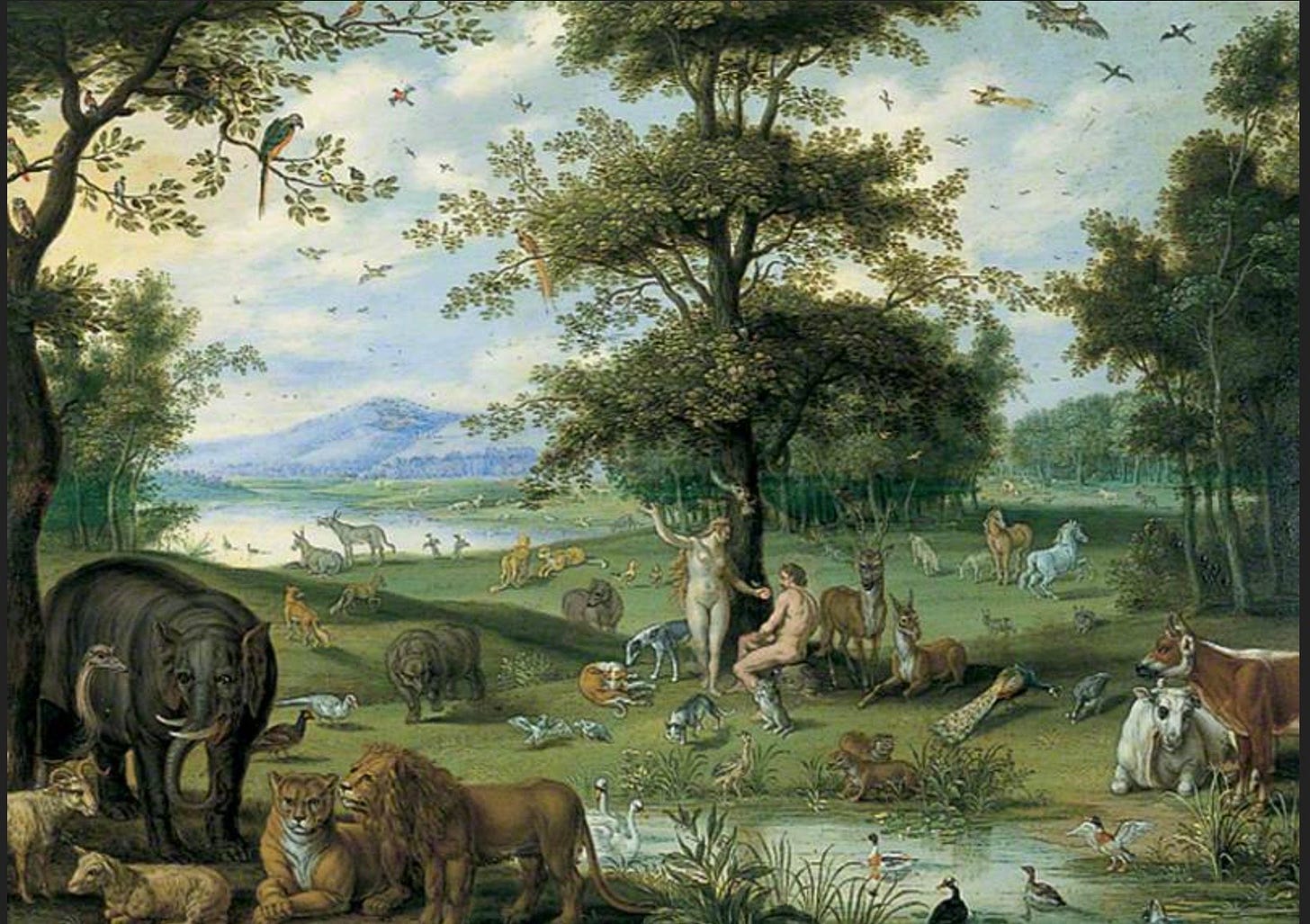

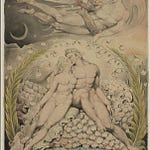

Last week, we watched dusk fall, both from space and from Earth, and now Milton turns his attention to the two humans as they head towards home. I’m going to read today’s 80 line portion in three sections…

When Adam thus to Eve: Fair Consort, th' hour [ 610 ]

Of night, and all things now retir'd to rest

Mind us of like repose, since God hath set

Labour and rest, as day and night to men

Successive, and the timely dew of sleep

Now falling with soft slumbrous weight inclines [ 615 ]

Our eye-lids; other Creatures all day long

Rove idle unimploid, and less need rest;

Man hath his daily work of body or mind

Appointed, which declares his Dignitie,

And the regard of Heav'n on all his waies; [ 620 ]

While other Animals unactive range,

And of thir doings God takes no account.

To morrow ere fresh Morning streak the East

With first approach of light, we must be ris'n,

And at our pleasant labour, to reform [ 625 ]

Yon flourie Arbors, yonder Allies green,

Our walk at noon, with branches overgrown,

That mock our scant manuring, and require

More hands then ours to lop thir wanton growth:

Those Blossoms also, and those dropping Gumms, [ 630 ]

That lie bestrowne unsightly and unsmooth,

Ask riddance, if we mean to tread with ease;

Mean while, as Nature wills, Night bids us rest.

Adam seems to be the man we think we know - careful, rule-minding, perhaps stolid - as he explains to Eve and to us, the natural rhythms of sleep and labour, night and day. These are natural rules, this is how it works here.

It’s interesting to see that there is labour here - not the troubled, back-breaking labour which will follow the Fall, but labour nonetheless, and that labour is a Good Thing:

Man hath his daily work of body or mind

Appointed, which declares his Dignitie,

And the regard of Heav'n on all his waies;

I thought of the problem of not having work, from my own and then from Milton’s imagined point of view. I’m not talking simply of crust-earning labour, because Adam and Eve don’t have to work for their keep, but rather work of the meaning-and-purpose type, and how important, if meaning and purpose matter to you, those things are. For Adam, otherwise lounging around pointlessly like a Lotus-eater, like an animal, and for Milton, writing the poem that is his great life’s task, the daily work is vital proof of Man’s place in the universe. What animals do does not matter much to God - ‘of thir doings God takes no account’ - they simply are, and thus are free of the problems of meaning, purpose, obedience, free will, good and evil. They just have to be. Simple.

It’s not so easy for Milton, Adam, Eve, me.

The labour here, for Adam and Eve, is pleasant rather than back-breaking, yet even so Adam is aware that they need more hands in the garden;

with branches overgrown,

That mock our scant manuring, and require

More hands then ours to lop thir wanton growth:

A reader pointed out to the online group that this labour benefits Adam and Eve:

Those Blossoms also, and those dropping Gumms, [ 630 ]

That lie bestrowne unsightly and unsmooth,

Ask riddance, if we mean to tread with ease;

We have to keep creation in good order ‘if we mean to tread with ease.’ It’s as if creation is not the finished complete thing we thought we saw when we first caught sight of what seemed a perfect ‘pendant world’ (Bk2, line 1051). Adam and Eve must keep working to keep it perfect.

As Adam finishes talking, Eve picks up her side of the conversation;

To whom thus Eve with perfet beauty adornd.

My Author and Disposer, what thou bidst [ 635 ]

Unargu'd I obey; so God ordains,

God is thy Law, thou mine: to know no more

Is womans happiest knowledge and her praise.

My anti-patriarchy hackles rise a little but I’m trying hard to do as Denis Saurat does and just say, ‘Pah! Milton! Women!’

But even with such an aside, we need to talk about Eve’s birth, made as she was from Adam’s rib. Here she calls him ‘my author’, meaning my creator, and, more complicatedly, ‘disposer’. The disposer being the one who disposes, according to the Etymological Dictionary, who puts in order, who leads:

Adam is a kind of father to Eve, as she was born of him, and he is the one who decides how she fits into Edenic life.

They are both ultimately made by God, so in another sense they are siblings, and she is the younger. They are also a couple. A lot of layers, then between them, and yet, Eve also choses to tell Adam she’s not going to argue with him, which raises indirectly the idea that she might argue. She seems a perfectly submissive wife, who well knows, as it were by rote, what should be said, parrot-fashion, by such a wife:

what thou bidst [ 635 ]

Unargu'd I obey; so God ordains,

God is thy Law, thou mine: to know no more

Is womans happiest knowledge and her praise.

And yet…what happens next feels very different to this repeated catechism. It is a love song in quite another register to that of ‘bidst’ ‘unargued’ ‘ordains’ ‘law’ .

With thee conversing I forget all time,

All seasons and thir change, all please alike. [ 640 ]

Sweet is the breath of morn, her rising sweet,

With charm of earliest Birds; pleasant the Sun

When first on this delightful Land he spreads

His orient Beams, on herb, tree, fruit, and flour,

Glistring with dew; fragrant the fertil earth [ 645 ]

After soft showers; and sweet the coming on

Of grateful Eevning milde, then silent Night

With this her solemn Bird and this fair Moon,

And these the Gemms of Heav'n, her starrie train:

But neither breath of Morn when she ascends [ 650 ]

With charm of earliest Birds, nor rising Sun

On this delightful land, nor herb, fruit, floure,

Glistring with dew, nor fragrance after showers,

Nor grateful Eevning mild, nor silent Night

With this her solemn Bird, nor walk by Moon, [ 655 ]

Or glittering Starr-light without thee is sweet.

But wherfore all night long shine these, for whom

This glorious sight, when sleep hath shut all eyes?

How lovely, heart-felt is this song compared to the dutiful statement of acceptance preceding it! A reader pointed out the repetition of the description, as if Eve, looking at everything, remembering everything, can barely tear her eyes/heart away from the loveliness of creation. She is in love with Adam and with life itself. She seems a much more volatile, unpredictable creature than Adam. She knows the rules, as we can see, but she’s not interested in them. Look at the stars!!!

Adam responds, in what seems initially a rational, scientific mode, yet a change comes over him, too. Moved by the astonishing complexity and beauty of creation, he also becomes a poet;

To whom our general Ancestor repli'd.

Daughter of God and Man, accomplisht Eve, [ 660 ]

Those have thir course to finish, round the Earth,

By morrow Eevning, and from Land to Land

In order, though to Nations yet unborn,

Ministring light prepar'd, they set and rise;

Least total darkness should by Night regaine [ 665 ]

Her old possession, and extinguish life

In Nature and all things, which these soft fires

Not only enlighten, but with kindly heate

Of various influence foment and warme,

Temper or nourish, or in part shed down [ 670 ]

Thir stellar vertue on all kinds that grow

On Earth, made hereby apter to receive

Perfection from the Suns more potent Ray.

These then, though unbeheld in deep of night,

Shine not in vain, nor think, though men were none, [ 675 ]

That heav'n would want spectators, God want praise;

Millions of spiritual Creatures walk the Earth

Unseen, both when we wake, and when we sleep:

All these with ceasless praise his works behold

Both day and night: how often from the steep [ 680 ]

Of echoing Hill or Thicket have we heard

Celestial voices to the midnight air,

Sole, or responsive each to others note

Singing thir great Creator: oft in bands

While they keep watch, or nightly rounding walk, [ 685 ]

With Heav'nly touch of instrumental sounds

In full harmonic number joind, thir songs

Divide the night, and lift our thoughts to Heaven.

Lines 659 to 673 seems almost scientific, astronomical account, which focuses on the order and purpose of the starry movements. But Adam is moved by what he beholds, as he imagines the stars in the darkness:

These then, though unbeheld in deep of night,

Shine not in vain,

I think of Milton, able to imagine the Milky Way though no longer able to see it. The stars are still there, ‘though unbeheld’ and ‘shine not in vain’. Do you catch an echo of the sonnet, On His Blindness?

When I consider how my light is spent, Ere half my days, in this dark world and wide, And that one Talent which is death to hide Lodged with me useless, though my Soul more bent To serve therewith my Maker, and present My true account, lest he returning chide; “Doth God exact day-labour, light denied?” I fondly ask. But patience, to prevent That murmur, soon replies, “God doth not need Either man’s work or his own gifts; who best Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state Is Kingly. Thousands at his bidding speed And post o’er Land and Ocean without rest: They also serve who only stand and wait.”

After the unseen stars comes the most extraordinary statement. Everything human could be gone. We mustn’t think

though men were none, [ 675 ]

That heav'n would want spectators, God want praise;

Millions of spiritual Creatures walk the Earth

Unseen, both when we wake, and when we sleep:

All these with ceasless praise his works behold

Both day and night:

I’m interested that these millions of spiritual creatures (angels, I assume?) praise God as they behold (see) his works. We’ve seen them, up at the gates of Paradise. But they are everywhere. Adam, like a premonition of Wordsworth, feels them everywhere in nature:

how often from the steep [ 680 ]

Of echoing Hill or Thicket have we heard

Celestial voices to the midnight air,

Sole, or responsive each to others note

Singing thir great Creator:

The wonderful presence of these spiritual beings is most felt in their music, which ‘divide the night’ - perhaps like bells tolling watches of the dark hours?

oft in bands

While they keep watch, or nightly rounding walk, [ 685 ]

With Heav'nly touch of instrumental sounds

In full harmonic number joind, thir songs

Divide the night, and lift our thoughts to Heaven.

All my thoughts of Adam and Eve’s hierarchy is lost now - I’ve become interested in Milton modelling both of them as full individuals - very different - yet deeply connected and in tune, it seems with each other. We leave them as they head towards bed;

Thus talking hand in hand alone they pass'd

On to thir blissful Bower…

More next week.

Share this post