Hello and welcome to Episode 60 of Read Paradise Lost with me, Jane Davis, a podcast and Substack newsletter about my project to read all of Paradise Lost by John Milton, aloud, and with a sometimes word-by-word, sometimes line-by-line discussion. This is a one-take recording with no editing, so forgive noise of seagulls, my coughing, or sound of men drilling next door. Rough and ready reading is what you get.

See Episode 1 for an introduction to the project.

It’s hard to believe 60 weeks of reading Paradise Lost have taken place! We will read to the end of Book 4 today, and so we are about a quarter of the way through the poem, and we have many more exciting weeks to come. Though I’ve read and taught the poem perhaps 10, or more, times over many years of reading the biggest and best of literature in Liverpool University’s Continuing Education programme, like you, I have never read Paradise Lost in this slow, concentrated, intense way before. It is becoming the most extraordinary experience, which for me only compares with reading for and writing my Ph.D., which I did over three years when I was aged 24-27. In that period of study there was a similar level of absorbed concentration, but it was spread over many texts - the nine volumes of George Eliot’s letters, and all her prose works, the sci-fi of the late Victorians and the Edwardians and of Doris Lessing, the post-Darwinian views of Thomas Hardy. But here, here, we are in the brain and experiences and imagination and spirit of one man and his vision of Heaven and Hell and us, poor creatures, crawling between them. What an adventure! I’m grateful to you, Dear Readers, for coming along with me.

This week we conclude Book 4, in a portion of just 47 lines. Gabriel has threatened Satan, found in Paradise, crouching like a toad at Eve’s ear, and warned him to be off. Satan’s response is typically belligerent:

So threatn'd hee, but Satan to no threats

Gave heed, but waxing more in rage repli'd.

Then when I am thy captive talk of chaines, [ 970 ]

Proud limitarie Cherube, but ere then

Farr heavier load thy self expect to feel

From my prevailing arme, though Heavens King

Ride on thy wings, and thou with thy Compeers,

Us'd to the yoak, draw'st his triumphant wheels [ 975 ]

In progress through the rode of Heav'n Star-pav'd.

While thus he spake, th' Angelic Squadron bright

Turnd fierie red, sharpning in mooned hornes

Thir Phalanx, and began to hemm him round

With ported Spears, as thick as when a field [ 980 ]

Of Ceres ripe for harvest waving bends

Her bearded Grove of ears, which way the wind

Swayes them; the careful Plowman doubting stands

Least on the threshing floore his hopeful sheaves

Prove chaff. On th' other side Satan allarm'd [ 985 ]

Collecting all his might dilated stood,

Like Teneriff or Atlas unremov'd:

His stature reacht the Skie, and on his Crest

Sat horror Plum'd; nor wanted in his graspe

What seemd both Spear and Shield: now dreadful deeds [ 990 ]

Might have ensu'd, nor onely Paradise

In this commotion, but the Starrie Cope

Of Heav'n perhaps, or all the Elements

At least had gon to rack, disturbd and torne

With violence of this conflict, had not soon [ 995 ]

Th' Eternal to prevent such horrid fray

Hung forth in Heav'n his golden Scales, yet seen

Betwixt Astrea and the Scorpion signe,

Wherein all things created first he weighd,

The pendulous round Earth with balanc't Aire [ 1000 ]

In counterpoise, now ponders all events,

Battels and Realms: in these he put two weights

The sequel each of parting and of fight;

The latter quick up flew, and kickt the beam;

Which Gabriel spying, thus bespake the Fiend. [ 1005 ]

Satan, I know thy strength, and thou know'st mine,

Neither our own but giv'n; what follie then

To boast what Arms can doe, since thine no more

Then Heav'n permits, nor mine, though doubld now

To trample thee as mire: for proof look up, [ 1010 ]

And read thy Lot in yon celestial Sign

Where thou art weigh'd, and shown how light, how weak,

If thou resist. The Fiend lookt up and knew

His mounted scale aloft: nor more; but fled

Murmuring, and with him fled the shades of night. [ 1015 ]

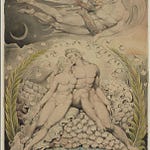

One of the many wonderful things about Milton’s vision is the way physical space, time, light, and being all expand or contract as required by the action or the dramatis personae. So here, Satan, ‘waxing more in rage’, ceases to appear in our readerly imagination as cherub, toad or argumentative captive soldier and is now ‘dilated’…

Like Teneriff or Atlas unremov'd:

His stature reacht the Skie, and on his Crest

Sat horror Plum'd;

The poetry reaches for the heights that evil can attempt when roused, confronted, scorned. There’s a careless, effortless put-down, too, in his naming of Gabriel as a mere boundary guard: ‘Proud limitarie Cherube’. He’s a damn good talker of the talk, Satan, as we’ve seen before;

ere then

Farr heavier load thy self expect to feel

From my prevailing arme, though Heavens King

Ride on thy wings, and thou with thy Compeers,

Us'd to the yoak, draw'st his triumphant wheels [ 975 ]

In progress through the rode of Heav'n Star-pav'd.

These are the moments when he seems heroic, huge, world-straddling, armoured, bellicose. But don’t forget that toad-like squat.

When he speaks, Gabriel’s troops respond with a shared motion, reminding us of Satan’s troops when he addressed them in hell.

While thus he spake, th' Angelic Squadron bright

Turnd fierie red, sharpning in mooned hornes

Thir Phalanx, and began to hemm him round

With ported Spears, as thick as when a field [ 980 ]

Of Ceres ripe for harvest waving bends

Her bearded Grove of ears, which way the wind

Swayes them; the careful Plowman doubting stands

Least on the threshing floore his hopeful sheaves

Prove chaff.

In the online group we wondered about the introduction of the ‘careful Plowman’ here - a recognisable rural image for Milton’s contemporaries. The simile ‘as thick as when a field/Of Ceres ripe for harvest waving bends/Her bearded Grove of ears, which way the wind/Swayes them’, seems easy enough, they move with that unified motion of a field of corn. Someone watching (the Plowman) does not know if his sheaves will (on the threshing floor) prove good harvest or chaff. So is this a note of doubt? Does Milton want us to wonder if the outcome of this meeting is in the balance? It’s at this crucial point that Satan distends and becomes Mountain Man. Yes, says Milton, everything was in the balance, not just Paradise, but also (widescreen, zoom out across time and space) Everything.

now dreadful deeds [ 990 ]

Might have ensu'd, nor onely Paradise

In this commotion, but the Starrie Cope

Of Heav'n perhaps, or all the Elements

At least had gon to rack, disturbd and torne

With violence of this conflict,

But something surprising happens. Th’ Eternal ( note the naming, not ‘God’, not ‘Father’, which would feel to be part of Christian story but ‘th’ Eternal’ which may feel even bigger than that)

Th' Eternal to prevent such horrid fray

Hung forth in Heav'n his golden Scales, yet seen

Betwixt Astrea and the Scorpion signe,

Wherein all things created first he weighd,

The pendulous round Earth with balanc't Aire [ 1000 ]

In counterpoise, now ponders all events,

Battels and Realms: in these he put two weights

The sequel each of parting and of fight;

The latter quick up flew, and kickt the beam;

Which Gabriel spying, thus bespake the Fiend. [ 1005 ]

The huge eternal presence/power weighs the situation in the balance, weighing everything , ‘all things first created’ plus or also ‘the pendulous round Earth with balanc’d aire’ and then ‘all events’. These things the Eternal weighs in balance with the sequels of parting and of fight - chains of consequences we can’t see but believe the Eternal does see. And it is over as fast as it started - one side of the balance ‘kick’t the beam’, and seeing this Gabriel now speaks to Satan.

But isn’t it incredible that Milton’s vision can take us to this Eternal, to this weighing scale, to all the possible consequences of both courses of action (fight or not fight)? And that having imagined it, he then allows Gabriel to see it?

I’m thinking of Milton as a very intelligent man working in politics, working for a particular end, with a chosen side, seeing alternatives as he goes, as we must, contingent, making the best choice you can at the time with the facts you can see... I’m thinking of him looking back later, when it is all over and so much is lost, including, probably, his faith in Oliver Cromwell, and many others. How looking back we see so much more, more easily. The balance is visible, the pieces fall into place. This not that.

Thus Gabriel doesn’t need to become Tenerife to win this spat. He just needs to point at reality:

Satan, I know thy strength, and thou know'st mine,

Neither our own but giv'n; what follie then

To boast what Arms can doe, since thine no more

Then Heav'n permits, nor mine, though doubld now

To trample thee as mire: for proof look up, [ 1010 ]

And read thy Lot in yon celestial Sign

Where thou art weigh'd, and shown how light, how weak,

If thou resist. The Fiend lookt up and knew

His mounted scale aloft: nor more; but fled

Murmuring, and with him fled the shades of night. [ 1015 ]

What does Heaven permit? That is the question. For the great poet who has not written but instead given twenty of his best years to active public work, trying to shape a revolution and a new republic based on individual freedom, given and lost, this is a hard thought to bear, whatever side you are on;

what follie then

To boast what Arms can doe, since thine no more

Then Heav'n permits, nor mine,

Satan, looking up, takes the point and (terse stage direction) ‘fled/murmuring’.

Murmuring what, I wonder? ‘Which way I fly is hell; my self am Hell…’

More next week.

Share this post