Hello and welcome to Episode 32 of Read Paradise Lost with me, Jane Davis, a podcast and Substack newsletter about my project to read all of Paradise Lost by John Milton, aloud, and with a sometimes word-by-word, sometimes line-by-line discussion.

This is a one-take recording with no editing, so forgive noise of seagulls, my coughing, or sound of men drilling next door. Rough and ready reading is what you get.

See Episode 1 for an introduction to the project.

A short portion of only 55 lines this week as we turn away from Hell and into the light, at the opening of Book 3. We turn from last week’s worrying ending - Satan hurrying towards the destruction he plans to wreak on Earth, and our little universe, hanging there so exposed and vulnerable in the heavens.

Could such a vision have existed before Galileo? Did Milton, when he visited the old heretic under house arrest, get a look through Galileo’s telescope?

Having achieved the visualisation of this amazing thought - our world in and of space - Milton turns now to his task as the poet about to write of God, and begins with a prayer;

Hail holy light, ofspring of Heav'n first-born,

Or of th' Eternal Coeternal beam

May I express thee unblam'd? since God is light,

And never but in unapproached light

Dwelt from Eternitie, dwelt then in thee, [ 5 ]

Bright effluence of bright essence increate.

A huge amount of theological history and thought is packed into these lines - so much so that Milton himself seems nervous (‘may I express thee unblam'd?’) about holding any particular line of thought here. Let’s have all possibilities, then. Are light and God the same? Possibly, ‘since God is light…’ but light is also ‘offspring of Heav'n first-born’. And God and light are also ‘eternal coeternal’. In the online reading group we turned back to Genesis for a look at the original.

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

Failed to render LaTeX expression — no expression found

I note that here God first appears as ‘the spirit of God’ - as if he/it has no form. Then - amazingly, now I think about it - light is created, and created by God’s speaking. ‘God said’ and ‘God called…’ run all the way through these opening verses, as if it is through language that creation takes place.

Milton meanwhile continues to muster his own language, making attempts to speak of God/Light without getting it wrong.

Or hear'st thou rather pure Ethereal stream,

Whose Fountain who shall tell? before the Sun,

Before the Heavens thou wert, and at the voice

Of God, as with a Mantle didst invest [ 10 ]

The rising world of waters dark and deep,

Won from the void and formless infinite.

I loved that idea of light ‘as a mantle’ - a cloak, but rather than a cloak which covers with darkness, this is a mantle of light that brings things to be from ‘the void and formless infinite.’ Rereading now, I wonder if the mantle idea comes from ‘the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters’… as the spirit were a kind of cloak, settling.

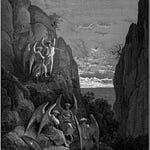

Milton now looks briefly back at his story so far, and I was struck by how close his experience as the writer is to Satan’s as protagonist. Everything we’ve seen of Satan has been Milton’s experience too. Stuck down there in the Stygian Pool for two whole books and then to ‘reascend, / Though hard and rare’.

Like Satan, Milton seems to be relieved to have escaped and be revisiting Light safely. For the writer, were those two thousand lines of Book 1 and 2 hell to write/experience?

How good now to feel the warmth of sun on your face:

Thee I re-visit now with bolder wing,

Escap't the Stygian Pool, though long detain'd

In that obscure sojourn, while in my flight [ 15 ]

Through utter and through middle darkness borne

With other notes then to th' Orphean Lyre

I sung of Chaos and Eternal Night,

Taught by the heav'nly Muse to venture down

The dark descent, and up to reascend, [ 20 ]

Though hard and rare: thee I revisit safe,

And feel thy sovran vital Lamp;

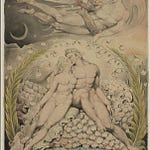

And now we move into an incredibly tender and personal mode, as Milton tells us about his blindness:

thee I revisit safe,

And feel thy sovran vital Lamp; but thou

Revisit'st not these eyes, that rowle in vain

To find thy piercing ray, and find no dawn;

So thick a drop serene hath quencht thir Orbs, [ 25 ]

Or dim suffusion veild.

I feel your light, but you don’t come to me, I’m left in the dark. Is this Hell? The awful image of the blind eyes rolling, of finding no dawn. I read this week that for blind people sleep patterns can be difficult because the lack of daylight means there is nothing to set the bio-clock that regulates our waking and sleeping.

Is that partly why Milton was up at nights, composing?

Yet not the more

Cease I to wander where the Muses haunt

Cleer Spring, or shadie Grove, or Sunnie Hill,

Smit with the love of sacred Song; but chief

Thee Sion and the flowrie Brooks beneath [ 30 ]

That wash thy hallowd feet, and warbling flow,

Nightly I visit: nor somtimes forget

Those other two equal'd with me in Fate,

So were I equal'd with them in renown,

Blind Thamyris and blind Mæonides, [ 35 ]

And Tiresias and Phineus Prophets old.

Milton’s nightly composition is a comfort to him, as is the thought of his predecessors, role models of blind poets and prophets: Thamyris, Maeonides, Tiresisas, Phineus, with whom he wishes to be listed. So, wakeful middle of the night is no problem but rather, extra time in which to create, thoughts turning into lines of poetry as naturally as birdsong:

Then feed on thoughts, that voluntarie move

Harmonious numbers; as the wakeful Bird

Sings darkling, and in shadiest Covert hid

Tunes her nocturnal Note.

That all seems good and is good, because the poem gets written, yet this resolute determination is followed by one of the most mournful and beautiful passages in English poetry.

Thus with the Year [ 40 ]

Seasons return, but not to me returns

Day, or the sweet approach of Ev'n or Morn,

Or sight of vernal bloom, or Summers Rose,

Or flocks, or heards, or human face divine;

But cloud in stead, and ever-during dark [ 45 ]

Surrounds me, from the chearful wayes of men

Cut off, and for the Book of knowledg fair

Presented with a Universal blanc

Of Nature's works to mee expung'd and ras'd,

And wisdome at one entrance quite shut out. [ 50 ]

Oh poor Milton, I can’t help but cry out. How he has loved the world. How he misses the sight of ‘flocks, or herds, or human face divine.’ If a Puritan is someone who doesn’t want anyone to have any pleasure, then Milton is no Puritan. These lines are full of love and pleasure. Pleasure which is lost. I think it is important that we feel the loss, that we suffer with Milton, so that his resolute return, back to the poem’s ambitious purpose can be felt with equal strength.

So much the rather thou Celestial light

Shine inward, and the mind through all her powers

Irradiate, there plant eyes, all mist from thence

Purge and disperse, that I may see and tell

Of things invisible to mortal sight. [ 55 ]

Because that’s the task, isn’t it, to see what cannot be seen with mortal, fleshly eyes? To feel ‘the mind through all her powers’, irradiated. The ‘thick drop serene’ that has quenched Milton’s physical sight cannot be purged or dispersed, but an inner blindness certainly might. Let me ‘justify the ways of God’ to man. Even, one might argue, after getting through Books 1 and 2, to myself. Let me see God in all this darkness. And tell.

That’s the prayer.

More next week.

Share this post